Our Curatorial Assistant Kari Adams was recently awarded a Jonathan Ruffer Curatorial Grant to travel to London and spend time at the Tate Archive and to Venice to visit the 58th Biennale. Here is a diary of her trip:

Uncovering the life and vision of Margaret Gardiner

Feeling a long way from Orkney, my place of work and the place I call home, I arrived at Tate Britain on a grey October Monday morning. Thankfully, it wasn’t long before I was surrounded by the comfort and light of some familiar friends – Hepworth, Nicholson, Gabo and Wallis – artists who are a part of my everyday life in Stromness and whose work form the original gift from Margaret Gardiner, founder of the Pier Arts Centre. Spending the first hour of my day with some of Tate Britain’s inspirational collection works from those artists mentioned above, along with others of their oeuvre, was in many ways the perfect beginning for the two days I was about to embark on in their incredible archive, reading through articles and correspondence relating to Margaret Gardiner. Prior to my visit I had requested the files Margaret deposited at Tate, largely composed of letters to Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, who were among her dearest friends. Margaret purchased works from both Nicholson and Hepworth – through her joy and passion for art, and as a means of supporting them through difficult times - and so too, from many of her other artist friends and acquaintances. The one underlining and indeed very important fact to point-out here was that Margaret never really wanted to acknowledge herself as a collector. And perhaps to that end, there is very little documentation of how she came into ownership of many of the works which now form the Pier Arts Centre’s core collection.

Shining a light

Being awarded the Jonathan Ruffer Curatorial Grant and afforded the resources to make the journey down to London to have dedicated time to read through Margaret’s letters was both extremely valuable and eye-opening. There were many interesting threads which may well indicate how she came to purchasing or owning various pieces which form part of our collection – including an interesting tale of Hepworth’s Involute II (1946), and Nicholson’s 1929 (fireworks). I was able to take photos for my own personal research and take notes which will now form a platform for further investigation.

Carrying-out research into how Margaret’s collection came into being seems extremely prevalent as we celebrate our 40th anniversary year. We have been reflecting on and highlighting points of significance throughout our exhibition programme and have displayed various articles of particular interest. Having now gained an additional bank of knowledge from this research trip, there are indeed further notable items we could now add to our archive – and subsequently, we can use this newfound information to form new lines of enquiry.

The profile of Margaret Gardiner is one which we endeavour to raise awareness of – her visionary foresight accountable for the purchase of many significant artworks of British Modern art, such as those in our collection, and for the commissioning of works by artists who were at the forefront of the avant-garde. Research this year has uncovered details of Margaret’s relationship with Naum Gabo, in particular the commissioning of a maquette for Spiral Theme – which is detailed in a letter between Margaret and Gabo held in the Tate archive - shedding new light on the friendship which existed between them; highlighting the way she actively supported artists who were making ground-breaking work of their time. How we use this information is important, in terms of Margaret’s biography, the legacy of the Pier Arts Centre and its Collection, and within the wider context of art and culture.

From London to Venice

After two full days of reading, I began the next leg of my trip fuelled with new knowledge and an appetite for more. Having never previously attended a Venice Biennale, I was intrigued, excited and eager to experience what was awaiting me. As I arrived, the iconic silhouette of the city appeared before me, bathed in golden Venetian sunshine, and I was soon to discover that the sheer scale and wonder of the biennale was going to far surpass any expectations I might have had. Suddenly all of the photos I had been exposed to following the 2019 biennale over the past few months came to life.

The Giardini

Exploring the national pavilions and exhibitions was a feast for the eyes and the soul. Starting with Spain and the work of Basque artists Itziar Okariz and Sergio Prego, I was confronted with a powerful message which appeared to run throughout this year’s exhibitions – an overriding voice connecting ideas of identity sexuality, subjectivity and environments shaped by power, communicated through mediums of artistic tradition. In this presentation, performance, film, body art and a postminimilism aesthetic are used as tools to carry-out a formal investigation between object and the space it occupies. Prego’s flesh-coloured, plasticised sculptures placed both inside the gallery and out into the garden beyond, both represent and question the malleability of materiality, and the fragility of one state in relation to another.

A particular highlight, not just from the Giardini but from the biennale as a whole, was seeing Cathy Wilkes’ new body of work for the British Pavilion. With visitor numbers restricted to 15 at any one time, as soon as you enter, you are afforded a welcoming sense of space away from the crowds – a breath in time. There is an eeriness, carrying with it a sense of loss; which sits alongside a feeling of loving, as value is placed on found objects and we are invited to make our own associations with their meaning, and also what we might consider beautiful. Walking through the exhibition there is a real focus on observation – the space given to the considerately placed artworks really captures you and forces you to look beyond any initial aesthetic. This is reinforced again as you are made to walk back through the galleries to exit the exhibition. Strikingly elegant and subtle, this exhibition left a real impression with me.

In contrast to the sensitively muted palette and somewhat serene atmosphere of Wilkes, I later found myself in the Brazilian pavilion, my senses overwhelmed, with their presentation of Swinguerra from video artist duo Barbara Wagner and Benjamic de Burca. I could hear the deep base resonating within the pavilion before I arrived and as soon as I was immersed within its walls I was completely mesmerized. Swinguerra takes its title from ‘swingueira’, a popular dance movement in the north-east of Brazil, fused with the word guerra, meaning war. Two large parallel screens provide a spectacular backdrop which speaks of identity and self-representation within both contemporary Brazilian and international culture as we experience times of significant political and social turmoil. Every beat, every movement of each individual dancer increasingly builds together – each a component of the overall rhythm – creating a poetic structure which carries a collective voice. The artists have portrayed the dancers with such care and respect, it has an unquestionable honesty and an understanding which shines through every step and every pulse. The identities of each dancer are both genderless and without origin – they are one, through the powerful expression of dance.

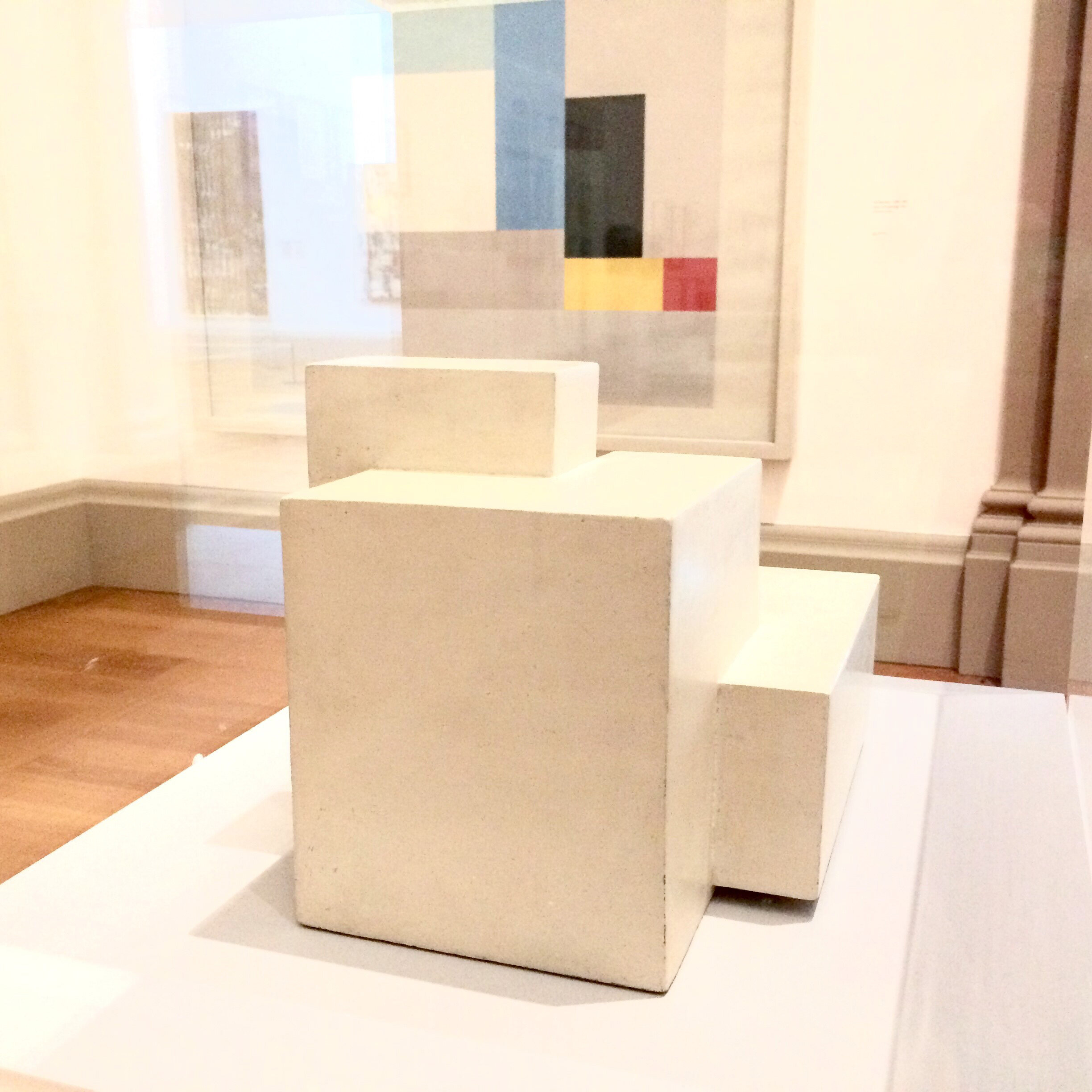

Other notable personal highlights from the Giardini include Laure Provoust at the French Pavilion and her fluid, reflective response which takes us on a surreal journey of the self, and makes us question who we are and where we are going; and Stanislav Kolíbal at the Czech Pavilion whose work continues similar themes and feelings of uncertainty, blurring the boundaries between painting, drawing, sculpture and architecture. At the end of my biennale adventure day one, I felt so full – satisfied and comforted by what I’d already seen, and charged for what was still to come.

Arsenale

Day two, and I set off under epically blue skies, en route to the Arsenale and its vast complex of exhibition spaces. With the quieter subtleties from the previous day still fresh in my mind, in almost startling contrast I was met with a series of ambitious, monumental installations. Curated by Ralph Rugoff, current director of the Hayward Gallery London, within the magnificent setting of the Arsenale, I found Liu Wei’s installation Microworld (2018), composed of geometric shapes and forms, simply magic - spherical forms and large polished aluminium plates sit behind a glass wall, conjuring notions of a Modernist stage-set. Our relationship with the environment is called into question as we are exposed to the artist’s reflection of the ‘microscopic world’ – as the viewer stands behind the glass and inspects what lies beyond, we are invited to make our own associations, and to revel in our own imaginations a while. Equally as mysterious, Korean-American artist Anicka Yi’s Biologising the Machine (tentacular trouble), a series of hanging, incandescent sculptures made of a stretched leather-like kelp which are cocoon-like in form. For the viewer, they are meant to conjure up ideas of organisms and of internal organs – their aesthetic is like a skin and they look like they could indeed be living things; which is further enhanced by the use of bacteria combined with Venetian soil which provide a swamp-like ground below the sculptures, emitting a very specific smell.

The underlying sense of the monumental, in both its quieter and louder guises, was especially prevalent in the Irish Pavilion where Eva Rothschild’s installation The Shrinking Universe, did not disappoint. As one of the Pier Arts Centre’s Collection artists, I had been very much looking forward to seeing her biennale showcase. I was immediately drawn into the atmospheric space, the work inviting the viewer in amongst their many angles and voids. There is something very tactile about Rothschild’s work which connects you through a desire to engage with its surface – and through this relationship, you become a part of the artist’s world. Large resin blocks, dusted with spray paint in bright sugary colours are stacked up against the wall – they have a heaviness yet they feel light; and this airiness is further enhanced by slender lines of black gloss, a metal structure which appears to be suspended on air, dancing in different through the space in directions. This is magnified minimalism and pure materiality. I didn’t want to leave Rothschild’s world of freedom and dizzying delights.

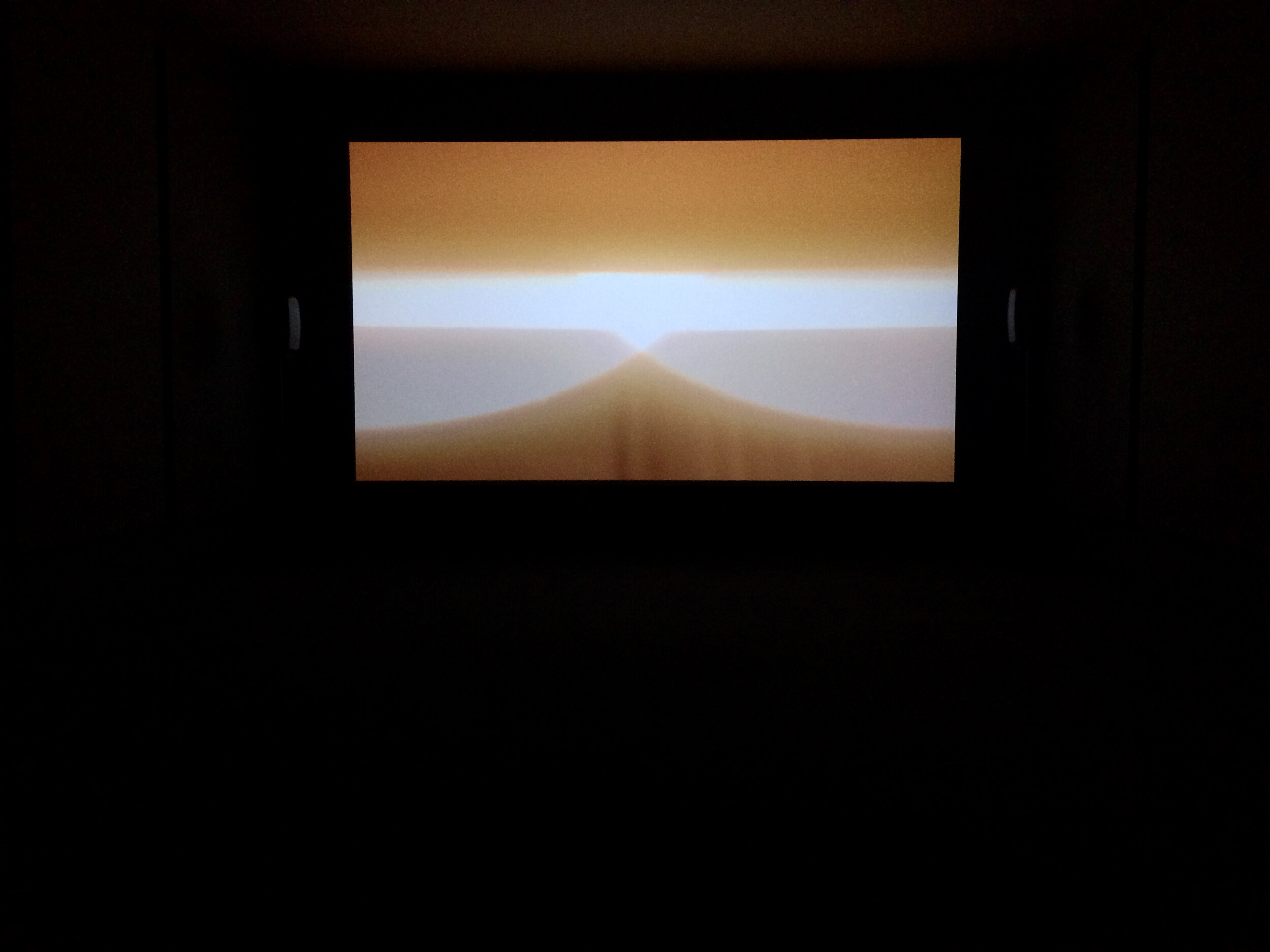

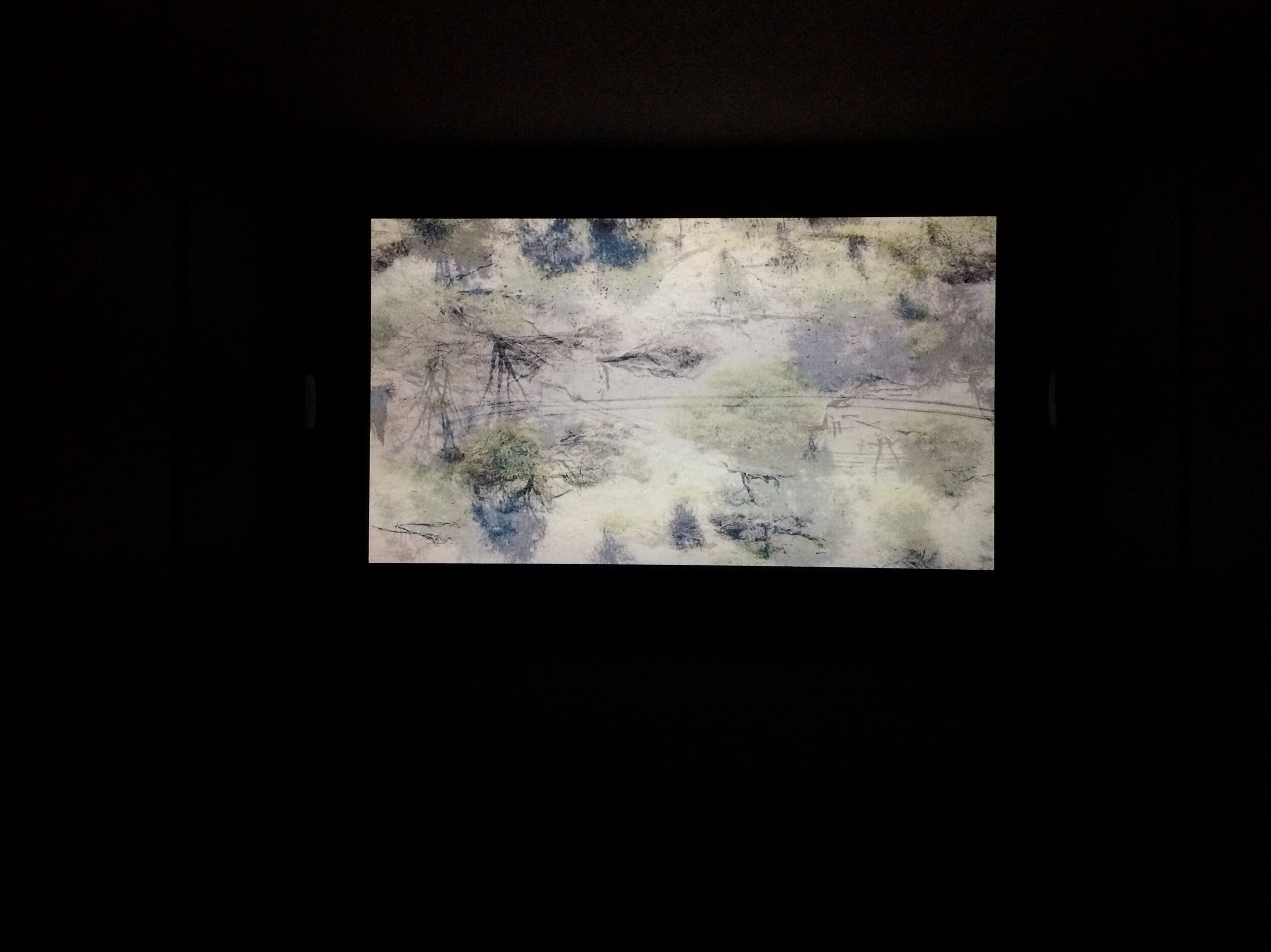

But what better way to end the day than with a visit to Scotland + Venice and the chance to experience Charlotte Prodger’s single channel video SaF05. The work’s title refers to the name used by naturalists in the Okavango Delta in Botswana for a lioness that exhibits certain male characteristics. Prodger’s fascination with this idea led her to filming the area where one is believed to be still inhabiting, however they never managed to get any footage of her. The idea of human behaviour being folded back into animal behaviour runs throughout, as Prodger explores key periods in her personal history. The viewer is presented with subtle yet powerful imagery shot from around the world, which is accompanied by Charlotte’s narrative – stories of growing up, loss and of first experiences. I was very much reminded of Margaret Tait, Orcadian filmmaker whose work we have in the Pier Collection, particularly by the way she explores time, place and memory in such a poetic, authoritative way. It is intimate, intense at points and incredibly captivating - this was a very welcome retreat, offering a sense of stillness away from the surrounding hustle of the biennale. As SaF05 is set to tour Scotland, I am hopeful that I may get the chance to experience this mesmerising film once more and that the Pier might be able to play a part in continuing its legacy and the work of Scotland +Venice.

May You Live in Interesting Times

This overview is a mere scattering of what I saw over the course of my time at the biennale – even still, there are no words to sum up quite how phenomenal it was. Attending the Venice Biennale has been an ambition of mine for a long time, and I feel extremely grateful that I have been able to finally make that dream a reality thanks to the Art Fund’s Jonathan Ruffer Curatorial Grants Programme. Being exposed to such a large volume of contemporary art within the truly magnificent framework of the biennale has been such a rewarding experience - and a reminder that we really do live in interesting times. I would regard it as a both a personal and career highlight and one that I am sure will undoubtedly inform new ideas and concepts as I progress further along my curatorial path.

As we continue a programme of contemporary collecting at the Pier Arts Centre, everything I have learned and absorbed during this research trip can fuel next steps. It has enhanced my understanding of the current international dialogue and has made me extremely excited about what can be achieved. The sense of possibility is the feeling I have been left with most – in terms of strengthening our roots, and what’s gone before, but perhaps most importantly, what can be done to shape and define our future.