by Curatorial Assistant Kari Adams

‘… I don’t feel that there’s a direct line in my life but that I was blown here and there by friendships and suggestions from others and by loves.’

(Margaret Gardiner, from a scatter of memories, p. 4)

the life

Margaret Gardiner c. 1932

Margaret Gardiner was born in Berlin on 22 April 1904, to parents Egyptologist Sir Alan Gardiner and Lady Hedwig Gardiner. Margaret had a privileged upbringing and described her childhood years as well-regulated but not unhappy – in her own words, it would have been ‘a kind of cheerful grey’ in colour. The family lived in the heart of the city and moved in well-respected social circles, and, during the summer months they holidayed in Hampshire (England) with Margaret’s paternal grandfather, or in Finland with her maternal grandmother. (Margaret’s English grandfather was a business-man in London and had sufficient family wealth)

The family were based in Berlin until the outbreak of the First World War, at which point they moved to England. Margaret, then aged six, began an early education - firstly, at the Froebel School in Hammersmith, before attending the left-wing progressive school Bedales in Hampshire. Margaret recalls that she stood as the Sinn Fein candidate in mock elections but, ‘only because nobody else would stand for it.’

‘I think Bedales was considered on the whole left-wing. I make a distinction about myself which is not a very flattering one: it is that I think that I’ve always been a rebel, but never a revolutionary.’

(Margaret Gardiner, from a scatter of memories, p.3)

Margaret spent 6 months in Vienna prior to beginning her studies at Cambridge with the intention of improving her German. She lived with a Jewish family and saw it more as a time to forge new friendships than commit to the complexities of the language. Margaret started studying at Newnham College, Cambridge in 1923; initially to read Modern Languages, before transferring to Moral Sciences (the Cambridge term for Philosophy); and, finally to Russian. For Margaret, the main purpose of her time at Cambridge was to meet new people – the excitement of new acquaintances and having the opportunity to discuss new ideas with them was to her ‘intoxicating’. (Footprints on Malekula, p.4)

‘They managed things very differently for women undergraduates in the Cambridge of my day… Certainly we were hemmed about by rules and conventions not experienced by the young women of today. But rules can be broken and conventions flouted and I don’t think we unduly fettered. Certainly at the outset it was strange – but it made you feel splendidly grown-up – to be addressed by everyone, both dons and fellow students, as Miss-so-and-so. All the same, there was something to be said for the gradual slide into anonymity and then that transition to first names which ratified a friendship.’

(Margaret Gardiner, from a scatter of memories, p. 62)

Margaret thrived within the social and intellectual circles of Cambridge, and became acquainted with many highly regarded literary figures such as T. S. Eliot (1888-1965), Herbert Read (1893-1968) and W. H. Auden (1907-1973).

Perhaps the most important friendship to blossom was that between Margaret and her first great love, ethnologist Bernard Deacon (1903-1927). Deacon obtained several First Class Honours degrees from Cambridge before parting to spend 14 months (from 1926-27) on Malekula, an island in the New Hebrides. During this time, their love developed through a series of letters. Whilst packing-up at the end of his field work, Deacon caught black-water-fever and tragically died, aged 24. Margaret was deeply saddened of the news, and not knowing quite how to deal with her grief she packed up all of Bernard’s letters, placing them in a box as a means to overcome her sadness. In 1983, which would have been the 56th anniversary of his death, Margaret travelled to Vanuatu to visit Deacon’s grave, and in 1984 published a memoir, Footprints on Malekula.

The memoir is composed of this series of letters between Bernard and Margaret , and, as a body of work, his writing conveys a very personal account of his lived experience there – an account which Margaret thought to be an important story to tell.

After her studies at Cambridge, the grief of Deacon’s death prompted a brief period of uncertainty for Margaret, before she made the decision to undertake studies at the Froebel Institute of Education to become an elementary school teacher. She took the necessary teaching exams and was duly appointed a position at Gamlingay elementary school in Cambridge. It was a short teaching career for Margaret - which she described as both exhilarating and disconcerting. She had very liberal ideas surrounding teaching - and indeed life - influenced by A. S Neill (1883-1973); which, ultimately clashed with the views of the school’s headmaster and those of the parents.

Following on from her teaching days, Margaret moved to Hampstead where she initially lodged with Jim Ede who was then an assistant at Tate – and later, the creator of Kettle’s Yard Cambridge. This move was partly to be closer to her friend Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975).

Margaret was introduced to Barbara through a mutual friend (Solly Zuckerman, 1904-1993) early in the year 1930. After an initial meeting over tea, Barbara invited Margaret to visit her in her studio and so their friendship began. Many more visits followed; talking, smoking and drinking tea into the midnight hours, ‘…spending long evenings with Barbara ending up with a beef steak or something – she really liked food.’ (Margaret Gardiner, as quoted, Time is a Country)

In a letter to Margaret, written many years after their initial meeting, Barbara wrote,

‘You know me better than anybody else and will understand how I feel. When I express a thought to you, you know what I mean.’

(Barbara to Margaret, from a scatter of memories, p. 164)

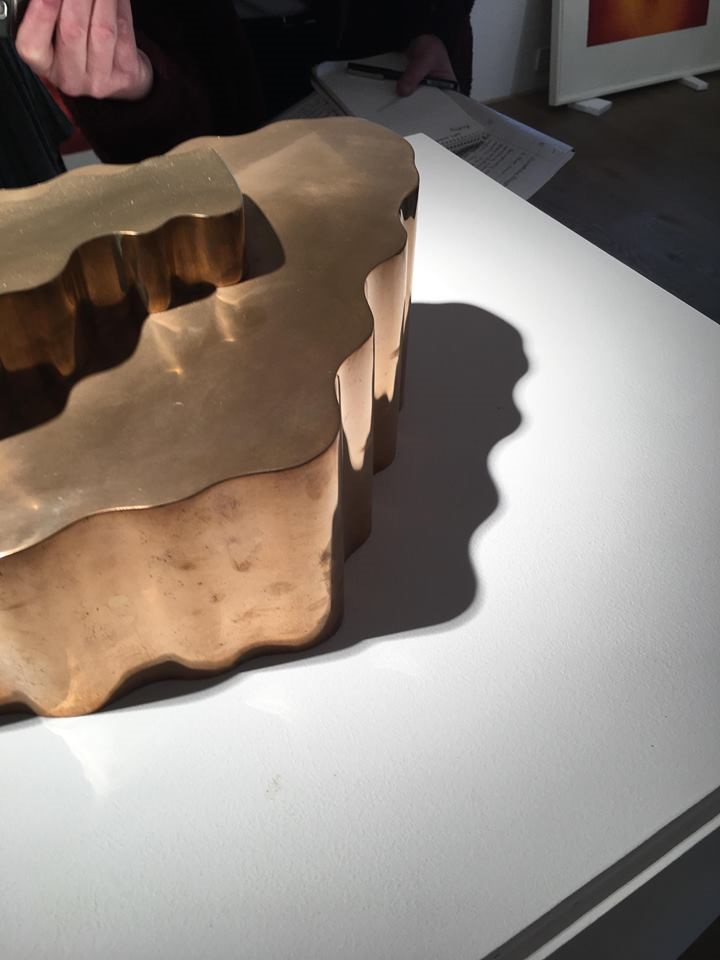

The friendship between Margaret and Barbara blossomed through deep layers of conversation on subjects from food to fashion, art to politics. They were both ‘fiercely partisan’ and showed great awareness and feeling towards current social problems and anxieties surrounding such things as unemployment, the coming to power of Hitler and the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. In later life, Margaret and Barbara travelled to Greece together; Margaret providing the guarea wood for some of Hepworth’s finest sculptures - as in Oval Sculpture, which would later be acquired by Margaret and included in her original gift to the Pier Arts Centre.

Barbara Hepworth Oval Sculpture 1943 © Hepworth

Margaret had a great admiration for Barbara and her approach to everyday life – inside and outside the studio - especially her work ethic as both a mother and as an artist. Margaret notes, ‘Work was at the centre of everything for her; it was what sustained her through the stresses and strains of her life’.

(Margaret Gardiner, from a scatter of memories, p. 164)

‘I knew nothing at all about sculpture, and only very gradually began to look at Barbara’s work in her studio in the Bell in Hampstead. And almost began to take it all in through the back of my head; and began to see what she was at and like it. And I also began to see what she had to say about it, and have feeling of the great excitement of that particular group of artists to which she belonged; with a feeling that they were creating a new world – that they were doing something to change the world, and change the rottenness of society – a tremendous idealism and exultation.’

(Margaret Gardiner, as quoted, Time is a Country)

Further to the great support Margaret offered to her artist friends, she played a significant role in the origins of the Institute of Contemporary Arts through her associations with Hepworth and Ben Nicholson (1894-1982), ‘It was because these artists were really struggling, were having a hard time to keep going at all.’

(Margaret Gardiner, from a scatter of memories p. 6)

Throughout her life Margaret was involved in great political activity, most notably, her endeavours in the anti-fascist movement, as well as her commitment to anti-war peace protests during the Vietnam War. Margaret was Secretary For Intellectual Liberty (FIL), an organisation formed between the wars composed of intellectuals to alert people to the dangers of fascism. It was a fairly small organisation but included many extremely well known members such as Henry Moore and E. M Forster. Its main objective was to be a rallying point for intellectual workers who wanted to call for an active defence of peace, liberty and culture in response to growing concerns over the condition of the world.

At different points in her life, Margaret Gardiner associated with the campaign against the Vietnam War, liaison with the Soviet Union and the cause of dissidents in Eastern Europe. Through her friendship with English artist Stanley William Hayter (1901-1988), Margaret developed an interest in peace protests and was introduced to advertisements in the New York Times by American artists against the war. As a result of this exposure, Margaret inaugurated a series of full-page advertisements in The Times to the same effect.

[Margaret’s active approach can also be found in two travel pieces about the Soviet Union, ‘Moscow Winter’, and the report of the World Congress of Peace Forces.]

Read a short extract, https://newleftreview.org/issues/I98/articles/margaret-gardiner-moscow-winter-1934

the gift

Margaret never defined herself as a collector, and only really became interested in ‘looking’ at art through her meeting with Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson. Furthermore, it was through this friendship that Margaret believed she started to develop a real taste and flare for visual things; which, during this period, was primarily focused on the work of a small group of artists - Hepworth, Nicholson, Terry Frost, Margaret Mellis, and Alfred Wallis; otherwise known as the St. Ives Group. Friendship formed the very core of her collecting and is essentially how Margaret’s ‘collection’ was built up. She always selected and purchased works on the simple principle of what she ‘really liked’; and, seeing her artist friends struggling to sustain their ambitions, she was always eager to support them in any way that she could.

‘Barbara and Ben always remained close friends and they were always grateful; they always harked back to the fact that I really had saved their bacon at that difficult period.’

(Margaret Gardiner, from a scatter of memories, p. 6)

Over the years, Margaret built up an inspired collection of works – works which brought her great joy. Since 1979, these works have formed the very core of the Pier Art Centre’s permanent Collection.

RY: Where did the idea to set up the museum [the Pier Arts Centre, founded in 1978] in the Orkneys come from?

MG: It really started off when Martin was doing national service and was absolutely hating it because he wanted to learn Chinese. And he was all set to go to the very good language school of the RAF when they suddenly decided that he was a security risk because of his father. (his father was a Communist)… And so he had to become an accounts clerk in the RAF and he was terribly bored with this. So he thought that if for his leave he could persuade them to let him go to Orkney, he would get two days’ extra travelling time and extend his leave in that way.’

Together, Margaret and her son Martin purchased a cottage on Rousay - and so, their love affair with Orkney contunied.

It became evident to Margaret that there wasn’t really anywhere suitable for local Orcadian artists to exhibit their artwork – they either had to display work in the library beside the books or in shops next to stock.

To that end, when Martin posed the question to Margaret, ‘What are you going to do with these works because I shall never live in a house with valuable works of art and I don’t think my children will want to either – so what are you going to do with them?’, Margaret replied, ‘Oh, I’ll give them to the people of Orkney’.

News of Margaret’s intentions travelled and excitement surrounding the prospect made her want to start proceedings straight away.

At the time, there were two buildings available on a pier of their own – an eighteenth century warehouse (formerly the whaling depot and recruitment office of the Hudson Bay Company), and an eighteenth century house just adjacent. The buildings appealed greatly to Margaret and so she began writing around to raise the money needed to purchase the buildings and house the collection.

Margaret’s careful planning together with her trusted relationships with various artists and gallery directors meant that she was able to transport her entire collection up to Orkney free of cost. Her collection works were displayed in various galleries including an exhibition at Tate London, before shows in Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Glasgow; all of which made for a great boost in terms of publicity and funding for converting the buildings. And that is essentially, how it all began…

Ben Nicholson was already old when Margaret was planning the Pier Arts Centre. He showed interest in her ventures but was also a little concerned about its location, commenting ‘It’s so far away.’ (from a scatter of memories p. 203) After further discussion, it appeared his worry stemmed from not enough people being able to see what he considered to be some of his best work. However, his friends fed him with gleaming accounts of the centre and it put his mind at ease.

‘Your Pier affair looks like a place I’d like to live in, it’s so nice – I think it’s so unlike what I don’t like in a gallery.’ (Ben Nicholson, from a scatter of memories p. 203)

Margaret writes that she was sorry Ben never got to visit the Pier, for it was her friendship with him, and of course Barbara, which ultimately led to the very making of the Pier.

the legacy

As we celebrate the 40th year of the Pier Arts Centre, the rooted and unfolding joy of Margaret Gardiner’s gift is brought to the fore. It is a time for reflection - a time to pause and revel in all that this gift has bestowed on the people of Orkney, and indeed on the great many it’s reached beyond. For the local community the Centre has provided a space in which people can engage with the Collection and its ever-evolving programme of exhibitions and events. It provides a welcome and calm atmosphere to find comfort in – as Margaret affirmed, it is a wonderful space for thinking. For local artists, it is a treasured resource which has undoubtedly shaped and inspired thinking and creative output. Our annual Christmas Open Exhibition continually supports this talent, showcasing a remarkable yield of creativity year on year. Visitors to Orkney consistently show their appreciation and amazement towards the Collection and its setting; especially the way in which the artworks and landscape harmonise together - the windows providing both a framework for what’s inside and a port-hole to the humming harbour beyond.

If you are a regular visitor to the Pier Arts Centre we hope that you are able to join us in the gallery to observe and participate in this celebratory year – whether it is for a quiet moment of thought, to experience and explore our exhibitions, or to attend one of the many events over the coming months. If you haven’t been before, I urge you to make a visit. Whether you have grown-up visiting the Pier or you have yet to walk through its doors, Margaret’s gift is here and has a story to tell for all who want to uncover it.

In a world which perpetually tries to divide and displace, Margaret’s gift – a collection which was brought together through the solace of friendship – needs to be celebrated now perhaps more than ever before. Undoubtedly as a meaningful and significant collection of twentieth-century art, but also for everything good that it stands for.

In the words of Emily (local nursery school visitor) my favourite part was: ‘Everything’.

For ‘everything’ Margaret - thank you.

Margaret Gardiner at the Pier Arts Centre c.1980

For more information about our 40th anniversary exhibition programme and upcoming events, please visit our website or subscribe to our social media channels.