In this Artist Profile we talk to Orkney artist Louise Barrington about her inspirations and how Japanese culture influences her work.

In this Artist Profile we talk to photographer Frances Scott about her interest in geography, her influences, and how she has been using Orkney memories to keep her going through the COVID-19 pandemic when she has been unable to travel home.

In this Artist Profile we talk to Birsay based artist Samantha Clark. Here’s what she had to say about her background, her own work and how Orkney has inspired her since moving to the islands four years ago.

In our first Artist Profile we talk to Orcadian artist Laura Drever about her own art and inspirations and how COVID-19 has impacted on her and her work as an artist.

Janine Smith, third year BA Fine Art student at Orkney College UHI, reflects on her experience curating an exhibition at the Pier Arts Centre.

Third year BA Fine Art student at Orkney College UHI Anna Charlotta Gardiner discusses curating an exhibition at the Pier Arts Centre as part of her Professional Practice module.

Our Curatorial Assistant Kari Adams was recently awarded a Jonathan Ruffer Curatorial Grant to travel to London and spend time at the Tate Archive and to Venice to visit the 58th Biennale. Here is a diary of her trip:

Uncovering the life and vision of Margaret Gardiner

Feeling a long way from Orkney, my place of work and the place I call home, I arrived at Tate Britain on a grey October Monday morning. Thankfully, it wasn’t long before I was surrounded by the comfort and light of some familiar friends – Hepworth, Nicholson, Gabo and Wallis – artists who are a part of my everyday life in Stromness and whose work form the original gift from Margaret Gardiner, founder of the Pier Arts Centre. Spending the first hour of my day with some of Tate Britain’s inspirational collection works from those artists mentioned above, along with others of their oeuvre, was in many ways the perfect beginning for the two days I was about to embark on in their incredible archive, reading through articles and correspondence relating to Margaret Gardiner. Prior to my visit I had requested the files Margaret deposited at Tate, largely composed of letters to Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, who were among her dearest friends. Margaret purchased works from both Nicholson and Hepworth – through her joy and passion for art, and as a means of supporting them through difficult times - and so too, from many of her other artist friends and acquaintances. The one underlining and indeed very important fact to point-out here was that Margaret never really wanted to acknowledge herself as a collector. And perhaps to that end, there is very little documentation of how she came into ownership of many of the works which now form the Pier Arts Centre’s core collection.

Shining a light

Being awarded the Jonathan Ruffer Curatorial Grant and afforded the resources to make the journey down to London to have dedicated time to read through Margaret’s letters was both extremely valuable and eye-opening. There were many interesting threads which may well indicate how she came to purchasing or owning various pieces which form part of our collection – including an interesting tale of Hepworth’s Involute II (1946), and Nicholson’s 1929 (fireworks). I was able to take photos for my own personal research and take notes which will now form a platform for further investigation.

Carrying-out research into how Margaret’s collection came into being seems extremely prevalent as we celebrate our 40th anniversary year. We have been reflecting on and highlighting points of significance throughout our exhibition programme and have displayed various articles of particular interest. Having now gained an additional bank of knowledge from this research trip, there are indeed further notable items we could now add to our archive – and subsequently, we can use this newfound information to form new lines of enquiry.

The profile of Margaret Gardiner is one which we endeavour to raise awareness of – her visionary foresight accountable for the purchase of many significant artworks of British Modern art, such as those in our collection, and for the commissioning of works by artists who were at the forefront of the avant-garde. Research this year has uncovered details of Margaret’s relationship with Naum Gabo, in particular the commissioning of a maquette for Spiral Theme – which is detailed in a letter between Margaret and Gabo held in the Tate archive - shedding new light on the friendship which existed between them; highlighting the way she actively supported artists who were making ground-breaking work of their time. How we use this information is important, in terms of Margaret’s biography, the legacy of the Pier Arts Centre and its Collection, and within the wider context of art and culture.

From London to Venice

After two full days of reading, I began the next leg of my trip fuelled with new knowledge and an appetite for more. Having never previously attended a Venice Biennale, I was intrigued, excited and eager to experience what was awaiting me. As I arrived, the iconic silhouette of the city appeared before me, bathed in golden Venetian sunshine, and I was soon to discover that the sheer scale and wonder of the biennale was going to far surpass any expectations I might have had. Suddenly all of the photos I had been exposed to following the 2019 biennale over the past few months came to life.

The Giardini

Exploring the national pavilions and exhibitions was a feast for the eyes and the soul. Starting with Spain and the work of Basque artists Itziar Okariz and Sergio Prego, I was confronted with a powerful message which appeared to run throughout this year’s exhibitions – an overriding voice connecting ideas of identity sexuality, subjectivity and environments shaped by power, communicated through mediums of artistic tradition. In this presentation, performance, film, body art and a postminimilism aesthetic are used as tools to carry-out a formal investigation between object and the space it occupies. Prego’s flesh-coloured, plasticised sculptures placed both inside the gallery and out into the garden beyond, both represent and question the malleability of materiality, and the fragility of one state in relation to another.

A particular highlight, not just from the Giardini but from the biennale as a whole, was seeing Cathy Wilkes’ new body of work for the British Pavilion. With visitor numbers restricted to 15 at any one time, as soon as you enter, you are afforded a welcoming sense of space away from the crowds – a breath in time. There is an eeriness, carrying with it a sense of loss; which sits alongside a feeling of loving, as value is placed on found objects and we are invited to make our own associations with their meaning, and also what we might consider beautiful. Walking through the exhibition there is a real focus on observation – the space given to the considerately placed artworks really captures you and forces you to look beyond any initial aesthetic. This is reinforced again as you are made to walk back through the galleries to exit the exhibition. Strikingly elegant and subtle, this exhibition left a real impression with me.

In contrast to the sensitively muted palette and somewhat serene atmosphere of Wilkes, I later found myself in the Brazilian pavilion, my senses overwhelmed, with their presentation of Swinguerra from video artist duo Barbara Wagner and Benjamic de Burca. I could hear the deep base resonating within the pavilion before I arrived and as soon as I was immersed within its walls I was completely mesmerized. Swinguerra takes its title from ‘swingueira’, a popular dance movement in the north-east of Brazil, fused with the word guerra, meaning war. Two large parallel screens provide a spectacular backdrop which speaks of identity and self-representation within both contemporary Brazilian and international culture as we experience times of significant political and social turmoil. Every beat, every movement of each individual dancer increasingly builds together – each a component of the overall rhythm – creating a poetic structure which carries a collective voice. The artists have portrayed the dancers with such care and respect, it has an unquestionable honesty and an understanding which shines through every step and every pulse. The identities of each dancer are both genderless and without origin – they are one, through the powerful expression of dance.

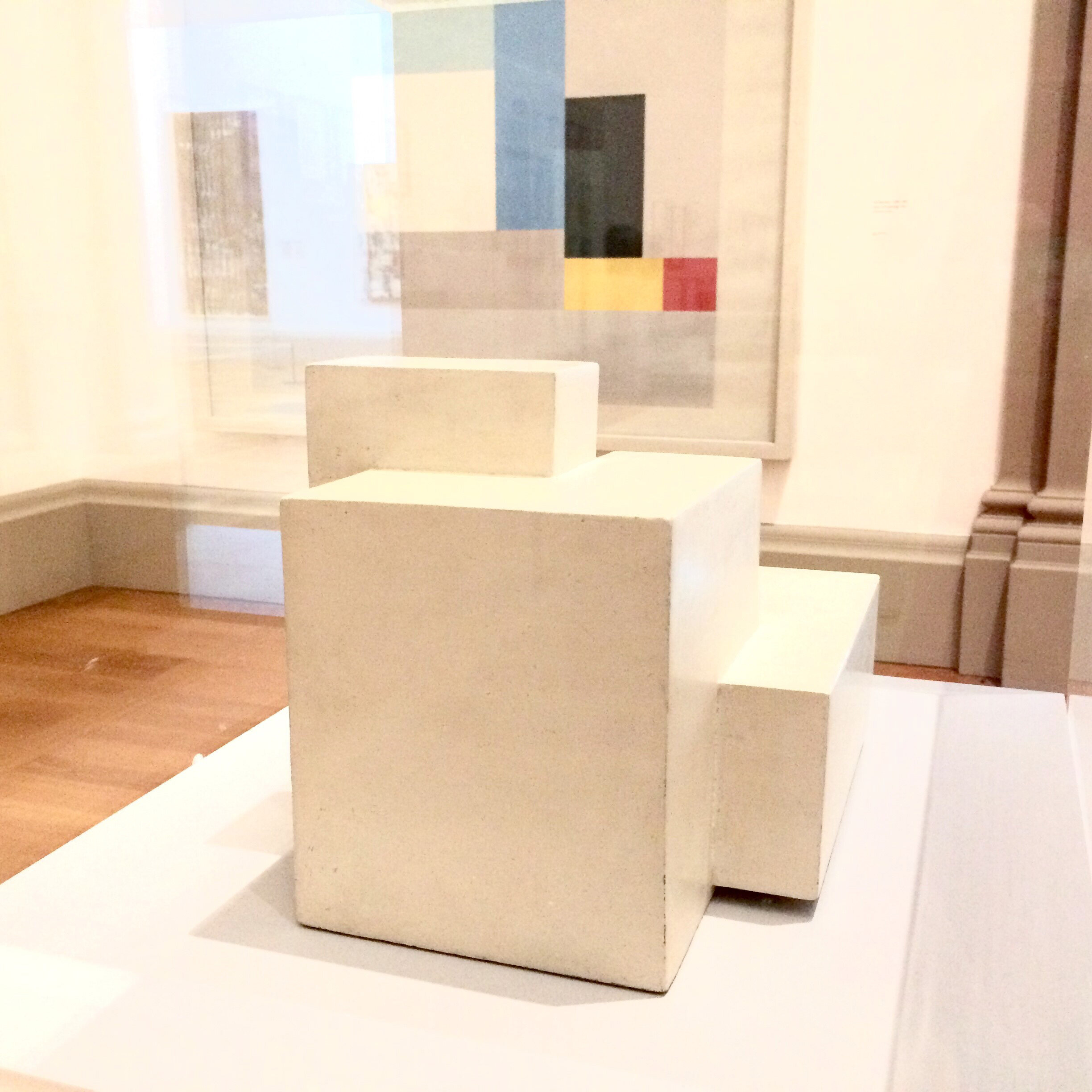

Other notable personal highlights from the Giardini include Laure Provoust at the French Pavilion and her fluid, reflective response which takes us on a surreal journey of the self, and makes us question who we are and where we are going; and Stanislav Kolíbal at the Czech Pavilion whose work continues similar themes and feelings of uncertainty, blurring the boundaries between painting, drawing, sculpture and architecture. At the end of my biennale adventure day one, I felt so full – satisfied and comforted by what I’d already seen, and charged for what was still to come.

Arsenale

Day two, and I set off under epically blue skies, en route to the Arsenale and its vast complex of exhibition spaces. With the quieter subtleties from the previous day still fresh in my mind, in almost startling contrast I was met with a series of ambitious, monumental installations. Curated by Ralph Rugoff, current director of the Hayward Gallery London, within the magnificent setting of the Arsenale, I found Liu Wei’s installation Microworld (2018), composed of geometric shapes and forms, simply magic - spherical forms and large polished aluminium plates sit behind a glass wall, conjuring notions of a Modernist stage-set. Our relationship with the environment is called into question as we are exposed to the artist’s reflection of the ‘microscopic world’ – as the viewer stands behind the glass and inspects what lies beyond, we are invited to make our own associations, and to revel in our own imaginations a while. Equally as mysterious, Korean-American artist Anicka Yi’s Biologising the Machine (tentacular trouble), a series of hanging, incandescent sculptures made of a stretched leather-like kelp which are cocoon-like in form. For the viewer, they are meant to conjure up ideas of organisms and of internal organs – their aesthetic is like a skin and they look like they could indeed be living things; which is further enhanced by the use of bacteria combined with Venetian soil which provide a swamp-like ground below the sculptures, emitting a very specific smell.

The underlying sense of the monumental, in both its quieter and louder guises, was especially prevalent in the Irish Pavilion where Eva Rothschild’s installation The Shrinking Universe, did not disappoint. As one of the Pier Arts Centre’s Collection artists, I had been very much looking forward to seeing her biennale showcase. I was immediately drawn into the atmospheric space, the work inviting the viewer in amongst their many angles and voids. There is something very tactile about Rothschild’s work which connects you through a desire to engage with its surface – and through this relationship, you become a part of the artist’s world. Large resin blocks, dusted with spray paint in bright sugary colours are stacked up against the wall – they have a heaviness yet they feel light; and this airiness is further enhanced by slender lines of black gloss, a metal structure which appears to be suspended on air, dancing in different through the space in directions. This is magnified minimalism and pure materiality. I didn’t want to leave Rothschild’s world of freedom and dizzying delights.

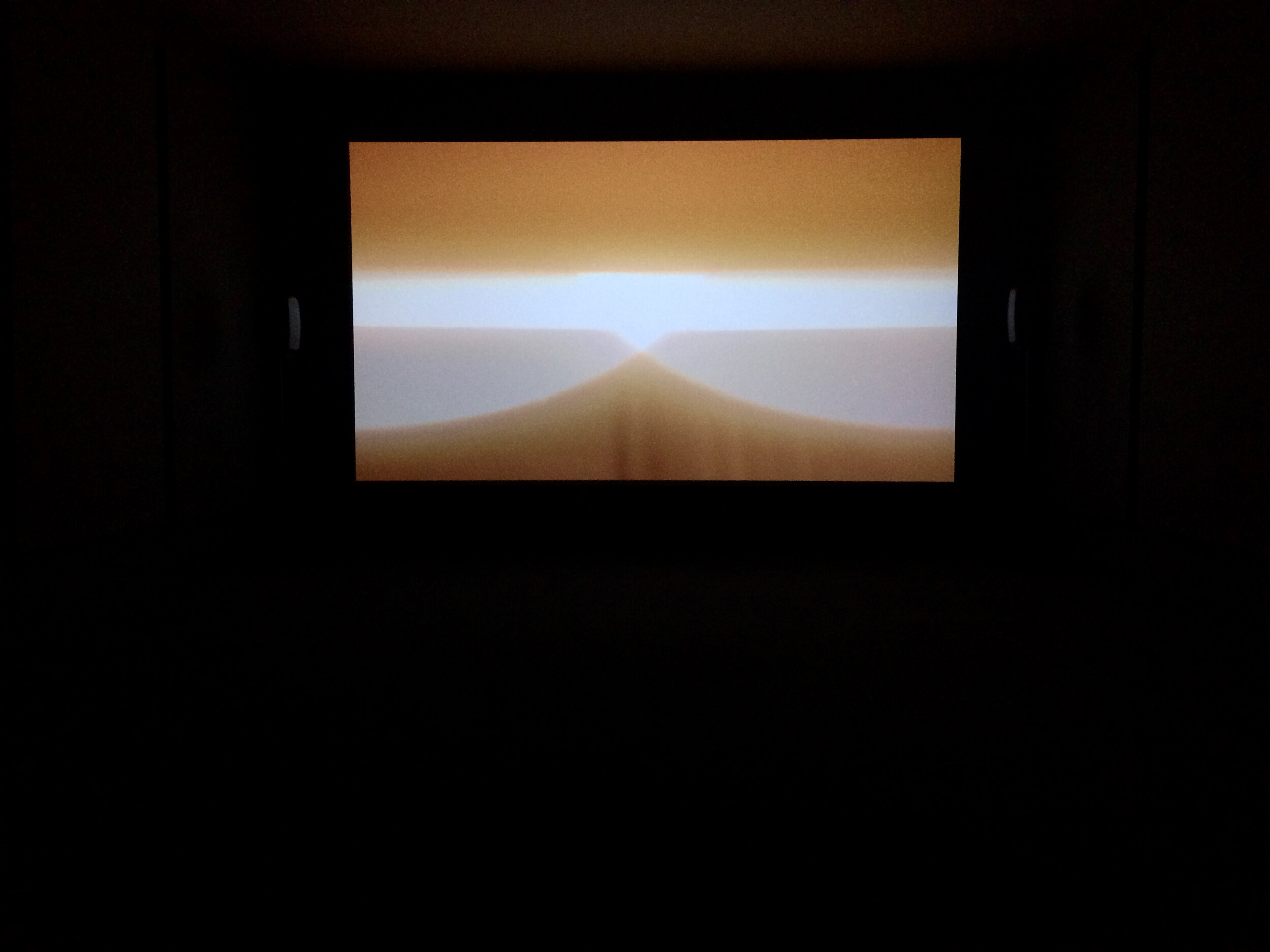

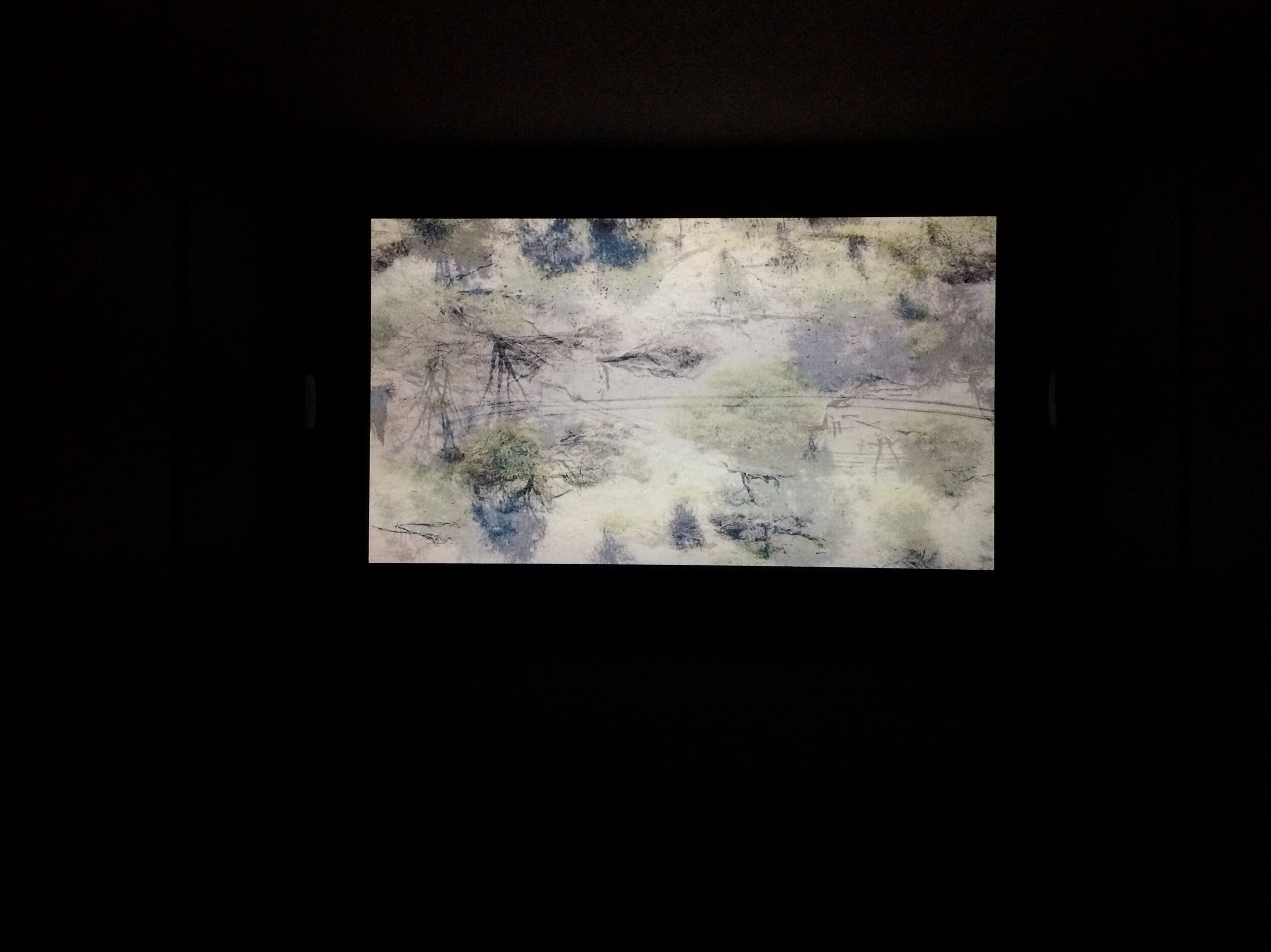

But what better way to end the day than with a visit to Scotland + Venice and the chance to experience Charlotte Prodger’s single channel video SaF05. The work’s title refers to the name used by naturalists in the Okavango Delta in Botswana for a lioness that exhibits certain male characteristics. Prodger’s fascination with this idea led her to filming the area where one is believed to be still inhabiting, however they never managed to get any footage of her. The idea of human behaviour being folded back into animal behaviour runs throughout, as Prodger explores key periods in her personal history. The viewer is presented with subtle yet powerful imagery shot from around the world, which is accompanied by Charlotte’s narrative – stories of growing up, loss and of first experiences. I was very much reminded of Margaret Tait, Orcadian filmmaker whose work we have in the Pier Collection, particularly by the way she explores time, place and memory in such a poetic, authoritative way. It is intimate, intense at points and incredibly captivating - this was a very welcome retreat, offering a sense of stillness away from the surrounding hustle of the biennale. As SaF05 is set to tour Scotland, I am hopeful that I may get the chance to experience this mesmerising film once more and that the Pier might be able to play a part in continuing its legacy and the work of Scotland +Venice.

May You Live in Interesting Times

This overview is a mere scattering of what I saw over the course of my time at the biennale – even still, there are no words to sum up quite how phenomenal it was. Attending the Venice Biennale has been an ambition of mine for a long time, and I feel extremely grateful that I have been able to finally make that dream a reality thanks to the Art Fund’s Jonathan Ruffer Curatorial Grants Programme. Being exposed to such a large volume of contemporary art within the truly magnificent framework of the biennale has been such a rewarding experience - and a reminder that we really do live in interesting times. I would regard it as a both a personal and career highlight and one that I am sure will undoubtedly inform new ideas and concepts as I progress further along my curatorial path.

As we continue a programme of contemporary collecting at the Pier Arts Centre, everything I have learned and absorbed during this research trip can fuel next steps. It has enhanced my understanding of the current international dialogue and has made me extremely excited about what can be achieved. The sense of possibility is the feeling I have been left with most – in terms of strengthening our roots, and what’s gone before, but perhaps most importantly, what can be done to shape and define our future.

Our Curatorial Assistant Kari Adams recently attended the National Galleries of Scotland’s Research Conference on Women Collectors. In this blog she shares her experiences at the event.

Communicating an Identity - recognising women collectors throughout art history

On Saturday 28th September I attended the Scottish National Galleries conference on the topic of Women Collectors presented as part of their annual Research Conference. The event gave host to 6 research papers, written and presented by influential women working within museums and galleries, exploring the role of the ‘woman collector’; in order to highlight, and, more often than not, uncover the significance of their endeavours throughout art history.

The reason for my attendance was to listen, to learn and to enjoy, but I was also there out of respect of the visionary foresight and remarkable gift of a collection by Margaret Gardiner (1904-2005) who founded the Pier Arts Centre in 1979. Without whom, the people of Orkney, and indeed the many beyond, would be unable to access and experience such a significant collection of British modern art. As we continue to celebrate our 40th anniversary year, celebrating other women benefactors through acknowledging and telling their stories on this day felt particularly poignant; and, on a personal level, made me all the more grateful for Margaret’s generosity and the importance of sharing her story too.

The initial question raised in the first paper, Two Hundred years of Women Benefactors of the National Gallery (presented by National Gallery Senior Research Curator Dr Susanna Avery-Quash and colleague, Curatorial Head of Department Christine Riding) of why is there no mention of women benefactors?, set the tone for the knowledge, ideas and considerations which followed. A repeating pattern very quickly emerged as to how this has happened; but the overall reasoning as to why is something which – as individuals and as public collections – we are still fighting for: giving women the recognition they deserve. Noteworthy points included were, 90% of artworks gifted by women in the National Gallery Collection are in the collection store at Trafalgar Square; and, in terms of documentation, the women donors’ names have become ‘separated’ from their gifts, giving way to their more significant male counterparts - which only adds to their invisibility, and underscores the thinking that ‘only the best’ bequests get pride of place. The National Gallery like many other institutions have been giving attention to women artists in recent years – for example, the acquisition of the seventeenth-century Italian Baroque portrait by Artemisia Gentileschi in 2018, which is to be followed by a major exhibition of her work in 2020 – the first solo exhibition on a historical female artist ever held by the National Gallery. This year has also seen a very significant bequest by artist Bridget Riley, who’s commissioned wall-based painting Messengers was influenced by their historic collection – engaging us in conversations surrounding the process of looking at art, and in relation to how we can adjust the gender-bias within national collections.

Image: Artemisia Gentileschi, 'Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria', about 1615-17, courtesy of The National Gallery

Image: Bridget Riley and our Director Gabriele Finaldi looking at 'Messengers' © 2019 Bridget Riley. All rights reserved/Photo: The National Gallery, London

Indeed, how we look and how we understand the world around us seems to lie at the very heart of this discussion. Each woman given mention, which included Georgiana Spencer, Queen Alexandra and Naomi Mitchison, created their own unique viewpoint – their gifted, sociable and intellectual endeavours making them both extraordinary women, within their own lifetime, and in terms of culture today. They were all women who created their own artistic and/or collection practices, giving voice and colour to a narrative - essentially communicating an identity which we must acknowledge. It is evident that an important feature of their contributions as collectors was not solely the buying but also the commissioning of artworks. Which, remains unquantifiable in terms of the foresight they had in giving recognition to artists who were driving forces of the avant-garde of their period. All of these women demonstrated taste and understanding for and of the artist of their time. And perhaps, the most common thread I found amongst this ground, was the gift they had for forming friendships.

Image: The Three Witches from Macbeth (Elizabeth Lamb, Viscountess Melbourne; Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire; Anne Seymour Damer) by Daniel Gardner, gouache and chalk, 1775

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Image: Photograph of the Princess of Wales, later Queen Alexandra, holding a No.1 Kodak camera at chest height. She is standing on the deck of a ship.

The No.1 Kodak camera was introduced in 1889 and took small circular photographs. There are many examples of these photographs in Queen Alexandra's album

© Royal Collections Trust

Dr Kate Cowcher, Lecturer in Art History at the University of St Andrews, presented From Kampala to Campbeltown: Naomi Mitchison and the Argyll Collection, and I couldn’t help but draw similarities between Mitchison and Margaret Gardiner. Both of these women really strived for what they believed in, more often than not for the greater good of others. Mitchison is highly regarded as one of the twentieth century’s most acclaimed writers and her friendships with artists such as Wynham Lewis are well-known. Mitchison’s idea for what is the Argyll Collection originated in the 1980s, which is perhaps the lesser known part of her story, raised questions of culture and education – ultimately, she wanted to give children who wouldn’t otherwise find themselves in an art gallery exposure to art. The ambitions of the collection were to expose Modern Scottish art, fuelled by her desire to buy ‘challenging things’. Mitchison showed a commitment to arts throughout her life, for example, the effect of WWII and the democratisation of the access of art, led Mitchison to auctioning commissions with Matisse and Picasso in the late 1940s. It was hard not to see the parallels with Margaret – both of these women through their friendships were actively supporting artists making ground-breaking work of their time. In 1941 Margaret commissioned Naum Gabo to make a maquette for J. D Bernal, supporting the production of new work during such difficult times allowed Gabo to ‘open a sluice-gate of creative waters’, for which he was extremely grateful. ‘I am very grateful to you, Margaret, for enticing me into doing that work. This construction has been in my mind for more than two years and I am glad that I made it now.’ (Hammer, M., extract from Constructing Modernity: The Career of Naum Gabo, (Yale University Press, 2000) p. 280. Gabo letter to Margaret Gardiner, 27th January 1942)

Margaret’s gift of her collection to the people of Orkney tells us many things about her story which we must not forget and we must acknowledge. Lack of documentation has perhaps been responsible for her role as a woman collector not being better known. That, and interestingly her dislike of the very word ‘collector’ itself – Margaret did not wish to be rendered as one, as she felt her artworks were as much or indeed more about the friendships they represented. Margaret’s many friendships with both literary and artistic figures, and particularly with the St. Ives artists – Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Margaret Mellis, and Terry Frost – are known and documented, mostly through correspondence amongst them. Margaret was very dear friends with Barbara Hepworth whom she was introduced to in 1930 through artist friend Solly Zuckerman. It was through this friendship that Margaret believed she really began ‘looking’ at art and started to develop a real taste and flare for visual things. She was very aware of the struggle her contemporaries faced, especially during the war years to keep producing artwork. Like the commissioning of the Gabo maquette, Margaret would purchase artworks from friends as a means to encourage their output and support them financially. Margaret’s ambition for the Pier Arts Centre was simple – she wanted to gift her works to a community who would otherwise not be exposed to such examples of British Modern art. Amongst other factors, creating a centre where local artists could display their work was of great importance. So to, Margaret was also very adamant there to be a ‘Children’s Room’ in the gallery when they were outlining plans for the Pier. A room which still functions with this intention at its core.

Image: Margaret Gardiner c. 1932 by Ramsay and Muspratt photographers

Image: Still Life by Margaret Gardiner

By the end of the conference, there was an overriding feeling that we were only just skimming the surface of who the women collectors we need to be recognising are, and to what extent they have contributed to collections. Each collector outlined represents a vast amount of research which has already gone into uncovering their individual stories. Which only leads to the fact that so much more has still to be done to fully expose the magnitude of their efforts. It is apparent, due to a lack of documentation in many cases, it sadly may well be the case that some stories are just forgotten. But all the more reason to do whatever we can to shine a light on the things we can find out. I am about to embark on a research trip to the Tate Archive in London, where I plan to look into the files pertaining to Margaret. We already know many wonderful and interesting threads of her story, such as those mentioned above, but I feel now more than ever it is important to keep going. How we use this information is also important, in terms of Margaret’s biography, the legacy of the Pier Arts Centre and its Collection, and within the wider context of art and culture. Margaret’s story only gets more compelling the further you explore, and it would be wonderful to think that through continued research we could inform many others of her life’s work. I would like to hope this is the first of many conferences which have the ability to raise awareness of women collectors, and maybe there will be more opportunity to share the joy of Margaret Gardiner in the future.

Image: Margaret Gardiner c. 1980 at the Pier Arts Centre

with Barbara Hepworth’s sculpture Curved Form (Trevalgan) 1956

As we continue to unfold Margaret’s original gift with contemporary collecting and a programme of education and events, how we feed this information into our efforts will hopefully underscore and encourage new and meaningful connections and relationships. As we look ahead to the very near future, the Pier is delighted to be working in partnership with the National Gallery, in collaboration with Contemporary Arts Society, with artist Rosalind Nashashibi who is the 2020 resident selected for their inaugural Modern and Contemporary programme. Click here to read more about the residency.

As we celebrate the birth of Alfred Wallis (1855-1942) this month, our Curatorial Assistant Kari Adams looks at his significance within the St Ives group and British Modern Art in our latest blog.

Alfred Wallis, Headland with two three-masters (recto) c. 1934-8, oil on card

The Early Years

Alfred Wallis was born on 18 August 1855 at Devonport, Plymouth. His father was a master paver from Devon, and his mother was Cornish and from the Scilly Isles – she died when Alfred was only a small child. At the age of nine, Alfred went to sea in the deep sea fishing fleet where he worked as a cabin boy and later as a cook - the schooner boats fished for cod in the North Atlantic waters off the coast of Newfoundland. In around 1880 he changed to inshore fishing, working on boats which fished for pilchards, herring and mackerel.

Alfred Wallis, Black Steamship c. 1934-8 oil on paper

In 1875, aged 20, Alfred married Susan Ward who was a widow twenty-one years his senior (she had borne 17 children, the eldest living was one of Alfred’s closest friends). Together they lived at her family home of 2 New Street, Penzance and had two daughters, but neither survived infancy.

The family moved to St. Ives in 1889 and Alfred decided to leave the sea for good, opening up a ‘Marine Store’, much like the one his brother owned in Penzance. He made some inshore fishing trips at this time, but the marine store soon proved a full-time occupation. Susan ran the store during the day whilst Alfred worked as a scrap merchant. The business thrived up until 1912 when he decided to retire and buy a house of his own. He then began to make ice cream, and is believed to be the first man who sold ice cream on the streets of St. Ives. Alfred and Susan suffered a period of disagreement in the years which followed, as it is believed she helped one of her sons financially, giving over the majority of their savings without Alfred’s knowing. By the time of her death in 1922, Alfred felt quite distressed by the situation and cut himself off from the rest of the family.

The Painting Years

Alfred Wallis, Seascape date unknown, oil on plywood

From this point he lived alone and became increasingly reclusive. For him, painting was the only thing he had ‘for company’. Alfred’s interest in painting had started when he was still working in the store - he would use bits of cardboard and any paints that came to hand. But now, at the age of 67, he gave painting his full attention and it very quickly became an obsession.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham had a studio only a couple of doors away from Alfred Wallis’ cottage. For two years, part of her daily routine included seeing Alfred coming and going, putting rubbish out, and occasionally the pair would chat. Barns-Graham remembers seeing “paintings all down the side of the – inside door[,] on the walls, there were paintings from the ceiling to the floor, done on the wall and on top of the table”.’

Wilkinson, D., The Alfred Wallis Factor: Conflict in Post-War St Ives Art, (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2017) p. 10

Photograph of Wallis’ studio in St Ives, from, Art About St. Ives (St. Ives Printing and Publishing Company in conjunction with Wills Lane Gallery: 1987 )

Alfred became very nostalgic living alone, reflecting on his youth and his experiences of deep sea fishing, but also on his surroundings of St. Ives. In a letter to friend and art collector H. S. Ede, dated 6 April 1935, Alfred explains, “what I do mosley is what used To Bee out of my own Memery what we may never see again as Things are altered all to gether”. [1] The local grocer, Mr. Baughan, often gave Alfred spare cartons, advertisement cards and packets from Quaker Oats – in a variety of different shapes – to paint on. Alfred would use the plain side to work on, often leaving the colour of the packet as the background, stating, ‘I do not put Collers what do not Belong’. Marine paint was his medium of choice as it came readily to hand, which may well have influenced his limited colour palette. Ben Nicholson gave him sketchbooks which he filled with crayon drawings – still favouring a limited palette of mostly blues, with occasional yellows and hints of red.

Early St. Ives photograph from, Art About St. Ives (St. Ives Printing and Publishing Company in conjunction with Wills Lane Gallery: 1987)

Alfred Wallis, White sailing ship – three masts c. 1934-8, oil on paper

Indeed, it was Ben Nicholson who ‘discovered’ Alfred Wallis when he and Christopher Wood went to St. Ives for the first time in August 1928. On passing Alfred’s cottage, they were both intrigued and excited by the paintings they could see through an open door. They knocked on the door, met Alfred and subsequently purchased some paintings from him. What was paid for the works was not recorded, however, it is believed subsequent paintings were bought and sent off in the post for sixpence a piece – a price Alfred thought was ‘fair’. The paintings bought by Nicholson and Wood that day were the first Wallis had ever sold.

Alfred Wallis and Ben Nicholson in St. Ives, courtesy Tate.org

One of Nicholson’s acquisitions ended up in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It is believed that Nicholson visited Alfred on one occasion to tell him about it and he showed him a reproduction of the work. Alfred’s response was full of disinterest, exclaiming, “O yes!” he said, “I’ve got one like that at home”.’

Wilkinson, D., The Alfred Wallis Factor: Conflict in Post-War St Ives Art, (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2017) p. 19

At the age of 86, Alfred wasn’t able to look after himself properly and became somewhat unwell. He was moved from his small home to Madrona Workhouse above Penzance, where he continued to paint. However, fourteen months later on 29 August 1942, Alfred died. As per his request, he was given a Salvation Army funeral, which was attended by many of his artist friends including Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Naum Gabo, Bernard leach and Adrian Stokes. A great many paintings still remained in Alfred’s house at the time of his death, of which Stokes managed to rescue a number of before the Council got the chance to incinerate them.

His grave at Porthmeor Cemetery is a raised slab which is covered with tiles made and hand-decorated by Bernard Leach. The tiles feature a lighthouse standing amidst waves, and depict a small man carrying a stick, on which there are the words: ‘Alfred Wallis, Artist and Mariner’.

Alfred Wallis, Three ships and lighthouse c. 1934-8, pencil and oil on card

The Artist

Alfred’s circle of St. Ives artist friends played a significant role in making his work more widely known through their support of his painting endeavours. Initial enthusiasm was sparked by Nicholson and Wood during the summer of 1928 when they were immediately inspired by Alfred’s unique vision. Along with all of those who befriended Alfred, they helped shape a legacy which now places him as one of the most important artists of British modern art.

‘When art reaches an over-sophisticated stage, someone who can paint out of his experience with an unsullied and intense personal vision becomes of inestimable value. The way in which he used the very simple means at his disposal – yacht paint and odd, irregular scraps of cardboard and wood – is an object lesson to any painter. Wallis shows such easy natural mastery of colour and forms that one can only look with delight and astonishment.’

- Exhibition Publication, Alfred Wallis (Arts Council: 1968), from the Introduction by Alan Bowness

Alfred Wallis works are represented in collections of modern painting throughout the world. The Pier Arts Centre’s collection holds 6 works, 3 of which are recto, verso and feature paintings on both sides as in the example below.

Alfred Wallis, Yacht, pink and green (recto) c. 1934-8 oil and pencil on card

Alfred Wallis, St Ives harbour and Godrey (verso) c. 1934-8 oil and pencil on card

In the gallery, his paintings sit alongside his contemporaries - works by Nicholson, Hepworth, Gabo, and Mellis; unfolding conversations about colour and shape, and the relationship between artist and landscape. Alfred was well respected amongst his friends and his creative output had a great influence on the work they produced at this time: in the words of Barbara Hepworth, “He certainly didn’t know how much we all learned and took off him.” (as quoted in, Icons of the Sea: Recollections of Alfred Wallis, in ‘The Listener’ 20th June 1968).

Alfred’s paintings and drawings speak of the sea and of a time gone by, but they can also be very much telling of the here and now. As we look at these works today, their intimacy has the ability to capture the viewer and provide a porthole to our own experiences – past, present or indeed future. In such moments, there is the potential to inspire, which carries with it the hope that his work will continue to delight and inform others throughout time.

A selection of Alfred Wallis paintings are currently on display in our Collection exhibition, THEN NOW WHEN.

Framed and unframed Alfred Wallis prints are available to purchase through the ArtUK website.

[1] Exhibition Publication, Alfred Wallis (Arts Council: 1968), from the Introduction by Alan Bowness

In this blog, Curatorial Assistant Kari Adams discusses how artists, including Naum Gabo, became acquainted with Margaret Gardiner through her endeavors with the Artists Refugee Committee.

Against the backdrop of Fascism in Europe, 1930s Hampstead saw a great influx of refugees, including many artists and creative people. Margaret Gardiner (1904-2005), the founder of the Pier Arts Centre, lived at 35 Downshire Hill, Hampstead, was instrumental in establishing the Artists Refugee Committee along with her friends and neighbours Roland Penrose and Fred and Diana Uhlman. Hampstead quickly became a centre of activity for practical and moral support for refugee artists, including Piet Mondrian, Moholy-Nagy, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and Naum Gabo.

Margaret Gardiner described Naum Gabo (1890-1977) as, ‘small and compact, with a look of slightly puzzled expectancy and a slow smile, he enchanted us all.’ (Margaret Gardiner, a scatter of memories p. 182). Gabo responded in new and unprecedented ways to the revolutionary political and scientific ideas of his time. And, together with his fellow artists, Gabo shared the same passions and beliefs – ultimately, the conviction that society could be changed for the better through the power of art.

Gabo is predominantly associated with the fundamentals of Constructivism* – which was supressed in his native Russia during the 1920s – and along with his brother Antoine Pevsner, has been a major influence on modern sculpture.

* Definition: Constructivism was a branch of abstract art founded by Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko in Russia around 1915. The movement was in favour of art as a practice for social purposes and saw the development of new techniques, influencing architecture, photography, photomontage and graphic design.

‘His own beautiful and lucid sculptures – constructions in space, he called them – in which ‘space is an absolute sculptural element, released from any closed volume’, were of great importance in this new conception of art. Space as an element in sculpture was not, of course, a new discovery – but Gabo’s use of it and his use of a new material – Perspex – was an exciting development.’

(Margaret Gardiner, a scatter of memories, p. 183)

During the war years (1936-1946), Gabo settled in England and produced many artworks concerned with modern geometry and physics, and the idea that empty space could be used as an essential element of sculpture. An example of such is Linear Construction No. 1 (1942-3), made from perspex and nylon monofilament (single fibre fishing line), which is included within the Pier Arts Centre’s current Permanent Collection display.

To discover more about Margaret Gardiner and her life-long active approach in defence of peace, liberty and culture, visit our exhibition Margaret Gardiner – A Life of Giving.

The exhibition is part of Insider/Outsider, a nationwide arts festival taking place from March 2019 to March 2020 to celebrate refugees from Nazi Europe and their contribution to British culture.